We didn’t leave the year 2021 without change; not one of us.

There was enough heart ache and joy to create hundreds of storylines for thousands of musicals…which I’m sure are being rehearsed as we speak!

But here, at Pacific Love Notes, we grew in more ways than just in the direction of music. I felt a personal call to do better- to learn and to grow. Like I always tell my students:

“If I’m lucky, I’ll learn every day until the day I die!”

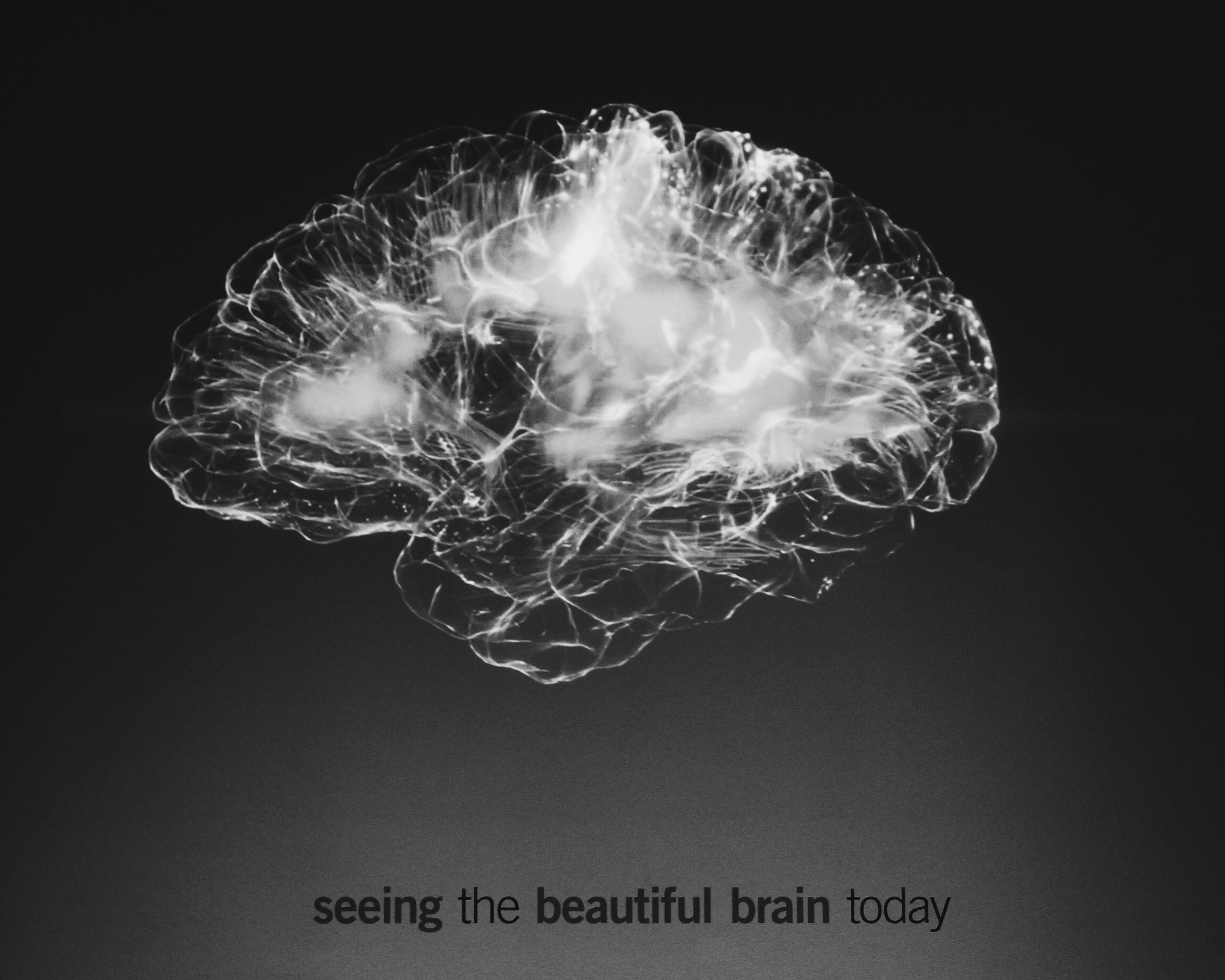

In the last year, I’ve taken over 15 graduate credits in the areas of social and emotional facilitation, including yoga certification, non-violent communication certification, and trauma-informed education! Through Pacific Love Notes, I want to bring this learning to our community! It’s time to open our hearts, minds, and doors to a mindful future!

Starting in 2022:

Pacific Love Notes will host weekly trauma-informed yoga sessions both via Zoom and in-person.

We will have monthly non-violent communication workshops to help families communicate in ways which draw them closer together in love, rather than continuing down the fractured path of distance!

And, we will hold regular self-care workshops for ALL.

Come join our play, as we work together toward healing.

With love, Carly

Founder and Managing Director of Pacific Love Notes <3